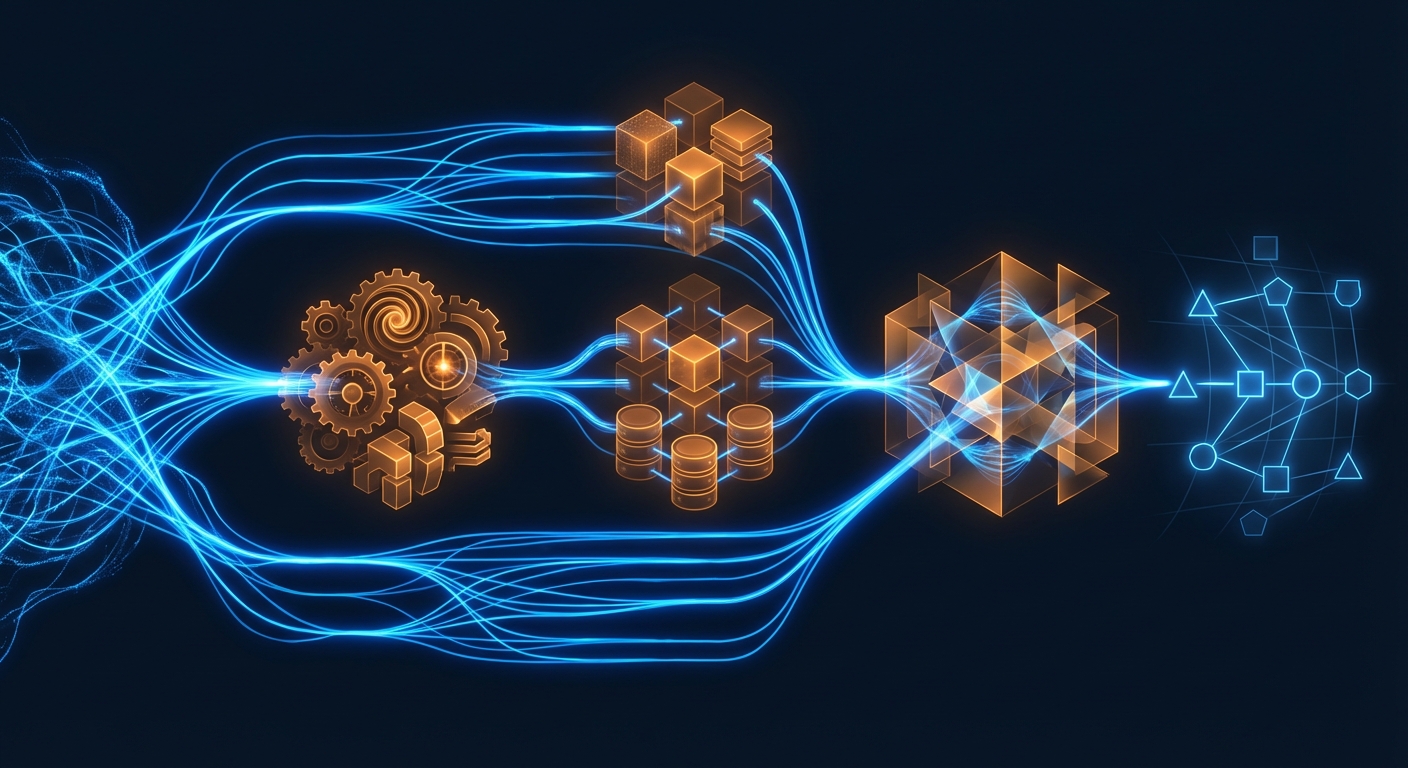

For those curious about the internals, here’s how a Mermaid diagram type comes together. This is the architecture I followed to build Wardley Map support.

The Stack

Input (DSL) → Langium Grammar → Parser → AST → Database → Renderer → SVG

Each layer has a specific job. Data flows one direction. No layer reaches back into a previous one. Let’s walk through them.

Layer 1: Grammar

The grammar file defines what’s valid syntax. Langium makes this declarative—you describe the structure, and it generates the parser:

WardleyMap:

'wardleyMap' EOL

(

TitleStatement |

WardleyComponent |

WardleyEdge |

EvolveStatement |

NEWLINE

)*

;

WardleyComponent:

'component' id=ID label=STRING coords=Coordinates EOL

;

Coordinates:

'[' visibility=NUMBER ',' evolution=NUMBER ']'

;

This is the entire component syntax definition. Langium handles tokenization, parsing, error recovery, and AST generation. Compare this to writing a parser by hand—it’s night and day.

The grammar also defines references between elements:

WardleyEdge:

from=[WardleyComponent:ID] '->' to=[WardleyComponent:ID] EOL

;

That [WardleyComponent:ID] syntax means “reference to a WardleyComponent by its ID”. Langium validates these references exist—you get errors if you reference a component that doesn’t exist.

Layer 2: Parser Bridge

The parser module bridges Langium’s AST to Mermaid’s database pattern:

export const parser: ParserDefinition = {

parse: async (input: string): Promise<void> => {

const ast = await parse('wardley', input);

populateDatabase(ast, db);

},

};

function populateDatabase(ast: WardleyMap, db: WardleyDB): void {

// Walk the AST and populate the database

for (const statement of ast.statements) {

if (isWardleyComponent(statement)) {

db.addComponent(

statement.id,

statement.label,

statement.coords.visibility,

statement.coords.evolution

);

}

// ... handle other statement types

}

}

This separation matters. The parser understands syntax. The database understands domain concepts. Different concerns, different modules.

Layer 3: Database

The database stores parsed data in a queryable format:

interface WardleyDB {

// Mutations

addComponent(

id: string, label: string,

visibility: number, evolution: number

): void;

addEdge(from: string, to: string): void;

setTitle(title: string): void;

setEvolution(componentId: string, targetEvolution: number): void;

// Queries

getComponents(): WardleyComponent[];

getEdges(): WardleyEdge[];

getTitle(): string | undefined;

getConfig(): WardleyConfig;

// Lifecycle

clear(): void;

}

The database is stateful—it accumulates data during parsing, then the renderer reads from it. After rendering, clear() resets for the next diagram.

Layer 4: Renderer

The renderer is where SVG gets generated. It’s the most complex layer—480 lines handling:

Evolution stage backgrounds:

function drawEvolutionStages(svg: Selection, config: WardleyConfig): void {

const stages = ['Genesis', 'Custom', 'Product', 'Commodity'];

const stageWidth = config.width / 4;

stages.forEach((stage, i) => {

svg.append('rect')

.attr('x', i * stageWidth)

.attr('width', stageWidth)

.attr('height', config.height)

.attr('fill', config.stageColors[i]);

svg.append('text')

.attr('x', i * stageWidth + stageWidth / 2)

.attr('y', config.height - 10)

.text(stage);

});

}

Component positioning:

function drawComponents(

svg: Selection,

components: WardleyComponent[],

config: WardleyConfig

): void {

components.forEach(component => {

const x = component.evolution * config.width;

const y = (1 - component.visibility) * config.height;

svg.append('circle')

.attr('cx', x)

.attr('cy', y)

.attr('r', config.nodeRadius);

svg.append('text')

.attr('x', x)

.attr('y', y - config.nodeRadius - 5)

.text(component.label);

});

}

Dependency arrows with proper path calculation between nodes, label collision avoidance so text doesn’t overlap, and theme support pulling colors from Mermaid’s theming system.

Layer 5: Theming

The theme module integrates with Mermaid’s theming system:

export function getThemeStyles(theme: string): WardleyTheme {

const baseTheme = getBaseTheme(theme);

return {

nodeColor: baseTheme.primaryColor,

nodeBorder: baseTheme.primaryBorderColor,

edgeColor: baseTheme.lineColor,

labelColor: baseTheme.textColor,

stageColors: calculateStageColors(baseTheme),

};

}

This means Wardley Maps automatically work with dark mode, forest theme, neutral theme—whatever Mermaid theme is configured.

Testing Strategy

The implementation has two test layers:

Unit tests (wardley.spec.ts) test each module in isolation—parser handles valid syntax, database stores data correctly, renderer produces expected SVG structure.

Integration tests (wardley.integration.spec.ts) test the full pipeline—input text produces expected rendered output.

What I Learned

Building this taught me a few things:

-

Follow existing patterns: Mermaid’s Pie diagram and Packet diagram were my templates. Copy structure, adapt content.

-

Langium is powerful: Declarative grammars, automatic validation, type-safe ASTs. The learning curve is worth it.

-

Tests catch edge cases: Label positioning edge cases, dependency cycle handling, empty diagrams—tests found bugs I wouldn’t have caught manually.

-

Docs are part of the feature: The documentation ships with the code. Nobody uses undocumented features.

What’s Next

The core implementation works. Next priorities:

- Regions: Visual groupings for market segments

- Pipelines: Horizontal groupings at same visibility level

- Annotations: Notes and callouts

- Cynefin diagrams: Different strategic framework, similar architecture

The architecture supports extension. Adding features means adding grammar rules, database methods, and renderer logic—each layer is independent.

Open source means this can grow with community input. The foundation is solid.